Like a good sailor knows their starboard from their port, a good sartorialist can spy a twill from a plain weave, a seer sucker from a glen plaid, and may even know the longitudinal direction of the warp from the latitudinal weft. To the average cloth-wearing human, the subtle characteristics that go into making good quality materials is arcane.

How to identify the names for cloth is the first step for many to understand the quality of a garment and its inherent ruggedness or delicacy. To successfully identify a fabric is a right that should not be reserved for the fashion fanatic, and it’s fascinating to know where a classic motif such as the stripe, got its start.

Since the late 18th century, the modern stripe has lined its way onto every applicable textile, from napkins to beach umbrellas. The ubiquitous stripe as we know it today is worn by men, women and children alike. The vertical are just as popular as the horizontal, and the wide is received just as well as the narrow. Stripes are as often woven into the cloth in twills and ticking, as much as they are strips of cloth in contrasting colors sewn together to make flags and athletic uniforms.

Such democratic times for the stripe weren’t always de rigueur. Before the 18th century, the stripe was reserved for the outcasts. The jesters, bastards, the insane and even prostitutes have been subjected to wearing the incriminating stripe throughout history. Social taboos of the Iron and Medieval ages aside and with a nod to the jailed men and pin-striped gangsters of the early 20th century, the stripe continues on as a classic motif in textiles because of its graphic ability to grab our attention. Standing out in rhythmic repetition, stripes create a strict pattern not often seen in nature. If used properly, a good stripe enhances the look and function of the object to which it is applied.

Right on cue, the men of B & C don their seer sucker suits when the temperature rises upward of 75 degrees. Recognized by the vertical on grain stripe along the warp of the cloth, seer sucker is made with a slack tension weaving process that creates a bubbling effect in the cloth. The cloth became popular for clothing worn in warm weather climes as the puckering fabric stays just above the skin instead of sticking to it, allowing for greater air circulation. The process for making seer sucker is slow, yet with its incredible low-tech functionality, lowly railroad denim to bespoke suits have kept stripes right where they belong— covering the seat of our pants and adding style to our lives.

Shop our collection of Stripes.

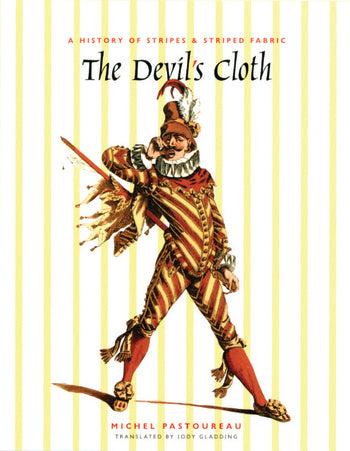

Further Reading: The Devil's Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric

"The stripe doesn't wait, doesn't stand still. It is in perpetual motion (that's why it has always fascinated artists: painters, photographers, filmmakers), animates all it touches, endlessly forges ahead, as though driven by the wind."

The Devil's Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric

The Devil's Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric

Michel Pastoureau. Translated by Jody Gladding

"Michel Pastoureau's lively study of stripes offers a unique and engaging perspective on the evolution of fashion, taste, and visual codes in Western culture."